Black Art is Black Life - An Invitation to Good Trouble: Civil Rights Past and Present

- Kentuck

- Mar 4, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 21, 2025

This post was written by Dr. Robin M. Boylorn, Kentuck's Primary Scholar for our 2021 exhibition season. Read more about her work as a professor, writer, autoethnographer, and activist below.

-----

As a creative writer, I have always been drawn to the arts—and the way visual arts invite sensory engagement and a new way of seeing, feeling and being during each encounter. Art insists that you pay attention, urging you to hone in on the details and layers and meanings and possibilities that get lost when you are not still and quiet enough to concentrate. Artists often create in those same conditions, listening for inspiration in the quiet, watching for nuance in the seeing, and weaving history into the folds of whatever medium and materials are available to them.

Mississippi born Val Gray Ward, cultural activist, artist and founder of the Kuumba Professional Theatre Company in Chicago describes one of the 12 principles of the Kuumba project saying, “Black Art is Black Life.” The term kuumba is Kiswahili for clean up, create, and build. Historically, Black people have taken the scraps and leftovers available to them to make something beautiful.

Their art and survival is instinctive and inherent

making something out of nothing

their life/their art.

life—crafting a future out of a problematic past art—threading together hope in the midst of trauma and despair

The resilience and permanence of Black life and survival is represented in the art and artistry showcased in the opening Kentuck 2021 exhibition Good Trouble: Civil Rights, Past and Present. Alabama Black artists offer stories of struggle, tenacity and possibility in portraits, paintings, pictures, sculptures, and quilts.

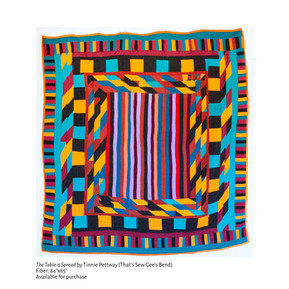

A quilt is the first thing you encounter at the start of the exhibit. Tinnie Pettway’s House Top Twist flanks the left wall with bright colors and squares, pieces of history and meaning that tell a story of resilience, briefly summarized in the history of Gee’s Bend on the accompanying placard. The fabrics are tied and twisted together with flyaway threads and mostly straight-lined patterns that fall into a design that is familiar to anyone who has ever stared at a quilt and imagined the ephemera included.

Congressman John Lewis’ famous quote about good trouble—necessary trouble guides you to art by local Black artists inspired by the Civil Rights movement—their work is decadent, reminiscent, colorful, intentional and full of truths like lynching, domestic terrorism, segregation, Jim Crow laws, and discrimination painted and threaded into the art and embedded in the lives of Black people living in Alabama for generations—evident in the lives of Black people living in Alabama now. Familiar faces like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks are joined by the faces from found photographs, collage prints, and figments of the black imagination—linking possibilities with platitudes and hope with the exhaustion of grief.

I focus on eyes, lips, hands, and fists as I walk through the exhibit, observing the translation of wood, acrylic, glass, steel, canvas, cloth, and dried mud into art.

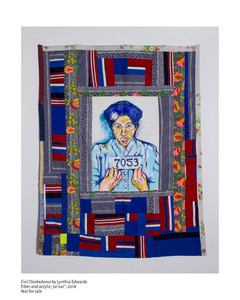

I am unsurprisingly drawn to Lynthia Edwards’ art. Her two quilts titled Civil Disobedience and Ya Mammy, and her acrylic painting of a Blue Magic pressing oil tin are black woman centered—inspired by “the ordinary existence of black girls raised in the South.” Her focus on recognizable and iconic black women, real (Rosa Parks) and imagined (the Mammy trope), and artifacts of everyday black womanhood (a pressing oil tin painted from their own childhoods) generates an offering and an altar. Lynthia feels it is her duty, as an artist, to tell the story of the Civil Rights Movement in her work, accounting for the ways black women’s activism and sacrifice are often missing from those narratives.

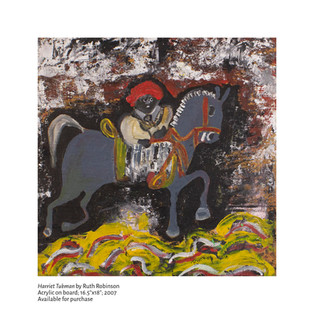

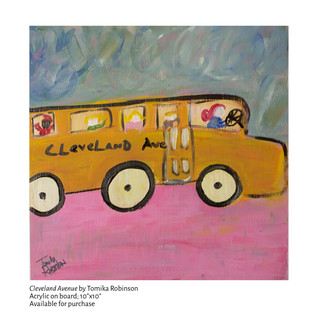

Her intentional projection of black womanhood is echoed in the work of other Alabama Black women artists including Bernice Sims, Ruth Robinson, Tomika Robinson, Minnie Pettway, Claudia Pettway Charley and Yvonne Wells. Bernard Wright learned to make mud paintings under the tutelage of his mentor “Jimmy Lee, the Old Man with Overalls On” who is erected in portraiture from natural ingredients and hands for tools. Wright says that he uses “anything from nature” to create art, including mud, and the juices from berries and muscadines. Similarly, Sir Chris Da R Tist uses whatever he can get his hands on. Identifying as an artist-activist he is committed to use his brush to speak for those who can’t speak for themselves. He calls his contributions to the exhibit, “trouble.” The intentional color and chaos of Masked I and Masked II, require you to focus on what is going in the pictures and not the abstraction.

Tony M. Bingham uses old books, found pictures, home movies, and video stills collected from second hand stores to offer his interpretation of The Negro Travelers’ Green Book in his contribution. Bingham sees his work as “investigations into the theme of safety, travel, destination and arrival” for Black people. The art maps the story of Black people traveling the terrain of the Black South. His accompanying animation film, “With a Green Book as My Guide” is accessible by QR code throughout the exhibit.

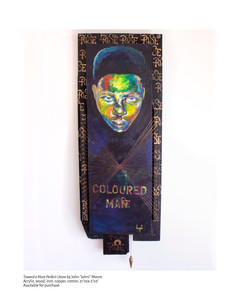

Each piece of art offers the face and reality of reflection from Jahni Moore’s E Pluribus Unum, to Darius Hill’s Soul Power, both using Black power fists as symbols of solidarity and futurism. Jahni Moore’s offerings also include As Above So Below, a blend of the browns and golds of clay to layer lips and eyes and blue, and Toward a More Perfect Union which offers a mixed media commentary on Black manhood.

The exhibit invites us to reflect on the good and bad, on the troubling times of then to the troubled times of now-- with echoes of the past and present stitched in between. The native Alabamian black artists featured in the exhibit tell a story of history that is close to home, close to the bone and grounded in lived experiences that demand reverence and remembrance.

See the Exhibition:

Museum Gallery

Click to enlarge photos

Teer Gallery

Click to enlarge photos

SoNo Gallery

Click to enlarge photos

------------

Good Trouble: Civil Rights Past and Present is on view in Kentuck's Museum, SoNo, and Teer Galleries until March 26, 2021. If you are interested in purchasing a piece from the exhibition, please email our Gallery Shop Manager Mary Bell at mbell@kentuck.org for more details.

Kentuck's exhibitions are sponsored in part by the Alabama State Council on the Arts, the National Endowment of the Arts, and the Alabama Humanities Alliance.

------------

Dr. Robin M. Boylorn is Associate Professor of Interpersonal and Intercultural Communication at the University of Alabama where she teaches and writes about issues of social identity and diversity, focusing primarily on the lived experience(s) of black women in the south. She is a scholar/activist, writer, speaker, autoethnographer and critical thinker who is committed to a life and work (life's work) that prioritizes social justice, is rooted in love, self-care, and accountability, and is housed with honesty and humility. She is the author of Sweetwater: Black Women and Narratives of Resilience, co-writer and co-editor of The Crunk Feminist Collection, and co-editor of Critical Autoethnography: Intersecting Cultural Identities in Everyday Life.

She has written public intellectual and culturally critical articles in venues including Slate and The Guardian, and her award-winning commentary, Crunk Culture (Alabama Public Radio) chronicles creative and sometimes cursory perspectives and responses to popular culture and representations of identity.

She is also a proud member of the Crunk Feminist Collective and the incoming Editor-Elect of Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies.

More information about Dr. Robin M. Boylorn is located here: robinboylorn.com